The MSA, or “multi-source agreement” is in effect a collection of gentleman’s handshakes between various equipment vendors and manufacturers in regards to interface modules, or “form factors” as they are technically known. They are not officially recognised standards or endorsed by organisations such as IEEE, ITU, ANSI etc.

What they are, are a set of technical specifications, such as physical product dimensions, optical interfaces, pin outs for circuit board contacts, software interfaces etc. that each vendor agrees to manufacture their products to. In theory this means you can take an SFP module from vendor A and put it in vendor B’s switch and reasonably expect it to work. “Interoperability” and “interchangeability” and the two key words to describe what the MSA aims to achieve between vendors.

The idea of allowing this mix and match approach, for the end user at least, is to allow equipment sourcing from more than one vendor and reduce costs through the economy of scale. In reality though, and this is the point a lot of MSA advocates neglect to mention, is that a lot of vendors – more so the perceived “high end” of the market – encode their optical modules. The MSA even allows for this in their specifications.

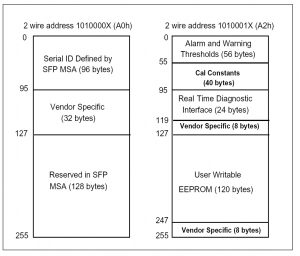

Each module, whether it be an SFP, an XFP or even a CFP has a block of data in the form of a 256 byte “memory map”, on the EEPROM. This is effectively a bunch of information the module gives to the switch the first time it is inserted so the switch knows what it is working with. The 8 bit address, A0h is used to define serial numbers firstly and concluded with some space reserved by the MSA specification for future use. Right in between those two entries lies 32 bytes of space labelled “Vendor Specific”. This space can be used to provide a code, unique to the vendor, to the switch. The vendor can then program their switch to look for this code and only accept a module that has a suitable code.

Effectively the whole purpose of the MSA has been destroyed by it’s own specification. Vendors can code their modules so their network devices only accept their own branded modules and then, quite legitimately, still advertise their products as MSA compliant. In fact they are compliant half of the time, and even then it relies on the other vendor being totally compliant. Here are some examples:

- A Cisco switch – coded to look for a vendor code, with a Cisco SFP – encoded. This works.

- A Cisco switch – coded to look for a vendor code, with a Netgear SFP – not encoded. This doesn’t work – the Cisco switch rejects the non-coded, MSA compliant Netgear module.

- A Netgear switch – not coded to look for a code, with a Cisco SFP – encoded. This works, the Netgear switch, MSA compliant, doesn’t even look at the code the Cisco module provides.

So just how is the MSA useful to an end user? It is unlikely that, for example, a school network manager will know who supports who in the world of networking. It is not unreasonable for someone in that position to read on a switch vendor A’s specification sheet “MSA compliant”, and then read on vendor B’s SFP specification sheet the same statement and put 2 and 2 together. If vendor B has SFP modules listed at a significantly lower price than vendor A, then is it not reasonable, despite the price difference, to assume the two will work together?

This whole issue can become even more problematic in the world of 3rd party modules, where a single module could be advertised to work with a sweeping range of vendor products. It is not uncommon to see some very low cost products not work in large numbers of vendor’s products simply because they are not coded. It is also not uncommon to see some of these suppliers proactively give out instructions to override code checks in certain vendor’s products (which immediately voids any warranty).

It is important for anyone purchasing modules from sources other than the equipment vendor to ensure the module is compatible. Advance are one manufacturer who code and physically test (not just guess) that their products are compatible with advertised vendors.